Archie Moore in conversation with Wes Hill

Considered one of Australia’s most inventive multi-disciplinary artists, Archie Moore’s practice revolves around slippages in language and identity, often evoking the ways in which cultural context affects meaning. Born in Tara, Queensland, but based in Brisbane for most of his life, Moore’s work has achieved widespread acclaim throughout Australia since he graduated from the Queensland University of Technology in 1998. On the occasion of ‘False Friends’—his first solo exhibition in Darwin at the Northern Centre for Contemporary Art—curator Wes Hill interviewed Moore about the ideas that inform his work, his wavering sense of identity, and the problem of being categorised as a ‘contemporary aboriginal artist’.

Wes Hill: Your work is about many things and spans a diverse array of media, but what comes through the most to me is your preoccupation with categorisation, how we systematise meaning, and how this process can serve to constrict identity. When and why did you become interested in this kind of approach to art?

Archie Moore: Well, on a psychological level I am always unsure of who I am, what I mean to myself and also what I might mean to others—sort of existing inside and outside myself simultaneously. I shift between these states and I don’t know where to be. Through racism, I became aware I was separate from the social identity of the small rural town I grew up in. Through them telling me I was someone ‘other’. I would also try to investigate my vacillating identities by looking at the relationship of my (alleged) father and mother, who were polar opposites of each other. My father was white, educated, hard-working, passionate, and religious. My mother was black, finished school in year four, didn’t work, was apathetic and non-religious. The kindness of my father and the apathy of my mother were complicated by the verbal abuse of the townsfolk, as well as the violent and angry compulsions of members of my extended family. My awareness of racism through words in the form of jokes was another confusing area; what the phrases are thought to mean, what they actually mean, what they mean from the speaker and to the listener. I’m always reassessing what things mean, going back and forth between several positions, never coming to a conclusion because I always see a range of perspectives at once. I used to have a hypnosis tape to aid astral travelling—which was something I had an open mind about, but was also trying to get some sort of objective proof of its existence—and there was a meditation component where I had to imagine that I was outside in nature. The sun was shining and I was standing in a park. I could never proceed from this point because I was wondering whether I was in the park viewing my surroundings or if I was supposed to be outside myself looking at my body in the park. Each time I listened to the tape I would adopt another perspective but I always seemed too aware of the other.

WH: I actually think this ‘astral travelling’ idea is never too far from your work, in a certain sense. Perhaps it’s your lightness of touch, or how you seem to move from project to project in an effortless manner. In terms of this confusion of identity that you mentioned, it seems that you manage to make works that are directly about your aboriginal identity, but I also sense a reluctance to let it define you completely. What are your thoughts about being perceived less as ‘contemporary artist Archie Moore’ and more as ‘contemporary aboriginal artist Archie Moore’. It’s a difficult question, I know, but I wondered if you have ever felt restricted by the label ‘aboriginal artist’?

AM: I think most of my work is about documenting that experience of being assigned a class or group to belong to. This notion is universal, but, to begin with, I was only interested in documenting this experience for myself. Now I’m also interested in the question of empathy in others. Now, I see even more pigeonholes. I’m not black enough for some white people, I’m not white enough for some white people, I’m not black enough for some black people. I don’t really mind what label people associate me with because I remain unsure of exactly who and what I am, and I enjoy that freedom of movement between categories. I enjoy the misrepresentations and misreadings too. I imagine a convoluted volume of information like all the rumours, hearsay, and conspiracy theories—partially true—that surround an event like the downing of the Malaysian Airlines flight MH370, where the actual reality is impenetrable. If there were to be a biography of me I’d like it to be white noise. I’m not sure if what I am saying now is even true. It’s certainly contradictory.

WH: You received a Samstag Scholarship to study in Prague in 2001. How did this experience impact upon the development of your practice?

AM: I’m not sure what impact, if any, it had on my practice. I’ve always been interested in language and how we garner meanings from words. It was non-degree study and so, apart from a short-lived attempt at getting the Czech- and English-speaking international students to discuss issues in a daily meeting, I was given a large studio to work in and that was about it. The lecturers didn’t have the knowledge of English to have any impact in terms of classes. I did a series of pastels on blackboard using words like ‘sob’ and ‘city’, which in Czech mean ‘deer’ and ‘emotions’ respectively. I guess my study enabled me to remember a Czech word recently for my work in Brooke Ferguson’s Sliding Door project at Boxcopy, where I used the word ‘arch’ which means the artist and the medium.

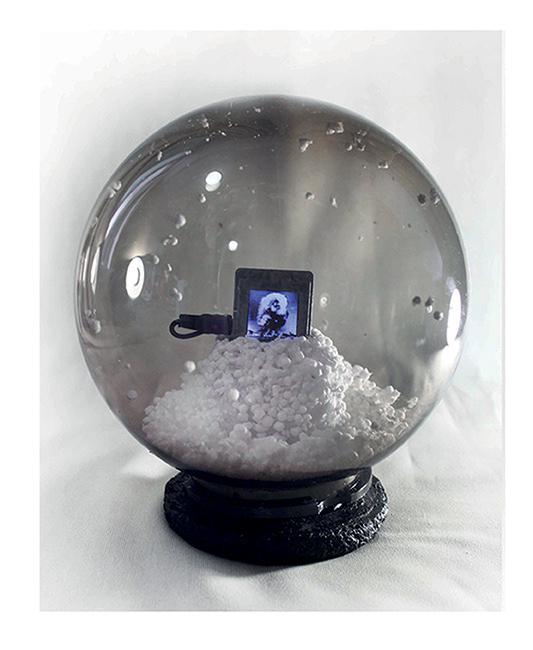

WH: Your work Snowdome (2013), which was shortlisted for the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards, is, I think, one of the most graceful political works I’ve seen. How did it come about, and what were you hoping to achieve with it, if anything?

AM: I think I began by looking at snow domes and asking what they represent; the tacky souvenir and tourist kitsch aspect, and the fact that every resort or tourist destination is sitting atop of some form of dispossession, massacre site or erasure of what was once there. Kill or transport the people from what is valuable and move them somewhere else less desirable, claim their land and then holiday there. Then, thinking of when aboriginal people do get their land back, it has either been contaminated or spent of all its worth, as in the case of Maralinga. I wanted to highlight these twelve nuclear tests conducted by the British at three locations on Australian soil because I don’t think it’s very widely known. I always get ideas when I look at materials first. I also found a snow dome which had an area inside it for a small photograph floating inside the water. I noticed it was about the same size as a keychain LCD screen so I used that. The idea of which images to have on the screen came about later.

WH: In Les Eaux d’Amoore (2014)—your exhibition at Amanda Rowell’s The Commercial gallery in Sydney—you worked with a master perfumer to recreate some smells that you associate with your South-East Queensland childhood. Is this exploration of memory a recent interest or has it informed your earlier work as well?

AM: Memory has been in all of my work somewhere. I’m still intrigued by who I am, what I think I am, and the reasons why. I’m a bit obsessed with my upbringing and the little knowledge I have about my ancestry. Another thing I’m interested in is this idea of shared experience or being in one’s shoes, or, more accurately, the unverifiability of knowing if another person’s experience is the same as your own. I’ve tried to force this upon the viewer in several shows. In ‘Depth of Field’ (2006), at Ryan Renshaw Gallery, I did a series of prints and objects with instructions to activate the works. The viewer had to engage in some sort of discriminating gesture to read a text, which implicated them further. For instance, one print was of what appeared to be black and white cubes, and the instruction was to put your index fingers at the corners of your eyes and pull away from your eyes. The abstract graphic would become a legible text which read ‘ching chong chinaman’. Also there was a plastic box inside another that you had to press your face on before the frosted pane at the bottom would reveal the words ‘boong nose’. Maybe it would remind some people of schoolyard racism in which they partook because the work received some angry and embarrassed reactions. Some people felt they had been made to engage in something they’re opposed to, or that I was putting words in their mouths. Some said it was juvenile, which is fine, because I think racism and other discriminations are all those things too. I wanted viewers to feel exploited and coerced too. My work Dwelling (2010) was a recreation of my childhood home that was inside a home that was sometimes an ARI: Accidentally Annie Street space, in Brisbane. People could walk through my memory of that space and look at actual objects from that space: old drawings/cartoons, mosquito coils, TV themes, the sound of me trapped in an old fridge, and so on. So this perfume idea at The Commercial gallery was that I got people to sniff my memories. I had eleven scents made to represent and evoke seven different memories for me. The aroma of clay and woodsmoke for my father; pencils and paper for the annual first day of school. I know that viewers could never have the same experience as me but I was interested in hearing what kind of reactions the smells had on them. If the people who visited the show ever smell these smells again they will be reminded of my show, hopefully. With all these ‘shared experience’ exhibitions, or ‘projective identifications’, as Djon Mundine has described them, I see them as a comment on reconciliation and the uncertainty of non-white and white people ever understanding each other, or ever having a sense of empathy for each other.

WH: Can you talk about your video work Kinelexic Tokyo (2012), and your fascination with text in general, which you often use in a ‘lost in translation’ sense—abstracted from the physical environment or context. I see this as a concern for dislocated speech, which, in terms of your aboriginal identity, could be seen as reflecting the type of governmental talk that seeks to appease but rarely results in fundamental change.

AM: I wanted to highlight text as a feature of our landscape, one as prominent as natural and urban features. It was intended to be a video about driving through Brisbane. Once the image was removed and only the text from the footage remained, I was curious about what you could ascertain from this. Could the viewer locate where and when it was shot? Do certain place/street names speak about history and colonialism? Would phrases in advertising suggest a certain political climate? I wanted to shoot it in a place like Oxford Street, Bulimba, or to have Ipswich in the background. That video hasn’t been shot yet, but I was in Tokyo for an exhibition and really wanted to travel along the route that the character Berton does in Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris (1972). I don’t know if what I shot was that route because I was a bit rushed and I was with my curator who had to translate what I wanted to the cab driver as best she could. I think the driver was a bit confused as to why we wanted to drive along a highway without any specific destination. Knowing that Tarkovsky’s film was, in part, about the failure of communication, or the limits of our understanding, I thought I would use this to do my video. After I realised it would take me twenty-four hours a day for six months to edit ten minutes, I didn’t get far with it—it’s another work-in-progress. But I am always looking at words and seeing other words within them, seeing them spell another word upside down. I probably see all words as potential ‘false friends’ [words in two languages that are similar in appearance or pronunciation but have different meanings], and I’m always attracted to finding out the underlying meanings or unintended connotations of words. That might stem from my experience with schoolyard racist jokes. My lack of contact with anyone outside this mindset compounded the problem; even my own family—and the only other aboriginal family in the town—would make racist comments about us. I guess this sort of trauma generates more dislocated speech, as you say. I think that a lot of words have no value, especially in advertising and politics. What does ‘fresh’ or ‘large’ mean anymore? Usually the opposite.

Archie Moore, Snowdome, 2013. Sculpture. Courtesy the artist and The Commercial, Sydney.

Archie Moore, Depth of Field, 2006. Exhibition detail. Courtesy the artist and The Commercial, Sydney.

Archie Moore, Les Eaux d'Amoore, 2014. Installation view. Courtesy the artist and The Commercial, Sydney.