Archie Moore: 1970 – 2018

It is the generosity in Archie Moore’s art practice that sets his work apart from much ‘Australian’ art. Not only is it emotionally generous, insofar as Moore offers a personal experience that allows audiences to connect with his work in an empathetic way, it is also generous in the way it illustrates an insatiable desire to understand the ways that soft and hard powers (and their emotional impacts) operate in the world. His curiosity, evident in visual and sensorial cues, through the scope of his practice, and through the inner world that he allows us in to, is the most generous thing that he could give.

When visiting Moore’s first major institutional exhibition, Archie Moore: 1970 – 2018 at Griffith University, one encounters emotional triggers that recall both happy and not-so-quaint histories. Just one example is the way in which the artist expresses memory in an open way, which allows the viewer to imagine freely, while the work remains strong in recreating a specific memory. Indeed, the title of the exhibition is itself a memorial of some kind. The exhibition is not a retrospective. Rather, its timespan indicates the years that Moore has been alive… an index of some kind.

Archie Moore: 1970 – 2018 is presented in multiple parts—outdoors, indoors, and in the walkway/ foyer into the Griffith University Art Museum. Each part is haunted by Moore’s yearning and by manifestations of his memory, presented from multiple standpoints. It is pertinent, then, that the names of the rooms recall different kinds of ‘cameras’. Accessed through three doors at the entrance to the exhibition, there are seven rooms, each presented as a separate work: Camera Affecta, Camera Familiaris, Camera Aviae, Camera Lucida, Camera Verbum, Camera Schola and Camera Obscura. Each room embodies a feeling, crystallised as a moment in time of Moore’s own memory, and yet they bring forth interpretative possibilities as vast as the experiences of those who encounter them. The Latin naming of the rooms recalls systems of classification—a common European practice also associated with the subjugation of Australia’s Indigenous peoples—as well as the way language can both embolden histories at the same time as obscuring them. If not extinct, many of Australia’s Indigenous languages are considered endangered, while they are also currently being revived through the efforts of many different Indigenous nations.

Born in Toowoomba, Queensland, Moore grew up in the small town of Tara, where imagination was essential to stave off boredom. It is a place rich in natural resources—close to the Condamine River (and the town of Condamine itself), where townspeople are battling the building of a pipeline to harvest coal seam gas. It is situated on Bigambul Country, now referred to as the Darling Downs, an area rich in greenery. It is the kind of place that you cannot really imagine unless you go there; swathed in heat in the summer, surprisingly bitey in winter, a place you would pass through on your way to somewhere else. And the kind of place where kids make their own games. It is not too dissimilar from the stock towns south of where he was born—Gamilaraay (Kamilaroi) Nation, on the borders, the most populous town being Goondiwindi—slightly less temperate, a little more dusty. The artist does not necessarily identify with the nation, but has cited Gamilaraay as his clan.1

A few of the rooms in Archie Moore: 1970 – 2018 bring this kind of environment to mind. Camera Aviae (2018), for example, recreates Moore’s memory of his grandmother’s room (or house) at Glenmorgan, also in rural Queensland. It is almost a version of the work shown at Tarnanthi in Adelaide in 2017, titled Whipsaw (2017), and a work for the 20th Biennale of Sydney (2016), A Home Away From Home (Bennelong/Vera’s Hut). In Whipsaw, the artist recreated a memory of a room, and accompanied it with the familiar Queensland sound of rain on the tin roof… there, you could imagine the rain seeping in. The red dirt and corrugated iron were also used in A Home Away From Home (Bennelong/Vera’s Hut), a reconstruction of Indigenous mediator and Wangal man, Woollarawarre Bennelong’s hut, which was ‘gifted’ to him by Governor Arthur Phillip in 1790. The original hut was the first piece of property that was built for an Indigenous person in the early stages of colonisation, and the inside was also reminiscent of Moore’s grandmother’s house. Cleverly, the artist imagined a room and associated it with his own memories, while situating both himself, and the viewer in a state of imagined familiarity, not only with the subject matter but also with feeling.

In Camera Aviae, however, there is no rain. There is the same red dirt floor, a lone forty-four gallon steel drum with a kerosene lamp perched on top, a broom made of twigs, and a harsh spring bed sans mattress. There is no door, just the hanging, colourful plastic strips that are used in warm rural places, where their purpose is to stop flies getting in, or to indicate a sense of semi-but-not-quite-privacy. It is perhaps one of the most affecting rooms—the quiet eeriness of it can only allow the imagination to run wild, and while one might not be able to situate one’s own memories within that room, one can absolutely have a sense of the life that was lived there.

The room dedicated to school (Camera Schola) is reminiscent of chalky regional schools, set with curriculums that obfuscate the lessons of Australian history. In this room, a chalkboard, replete with equations on a blackboard (featuring the inclusion/ exclusion principle), old school desks where you can imagine rulers hitting the wood, and an old film projector showing films that were a part of Moore’s childhood in the Queensland education system. The films themselves depict a white person telling of Indigenous history. The desks are filled with protractor and compass sets, scrapbooks, children’s books and folders, scrawled on and stickered, with some of the paraphernalia being similar to that of Moore’s alter-ego, Grubbanax Swinnasen. The alter-ego’s drawings are scratchy, demonic, lurid and often quite humorous. They draw attention to both (art) history and the boredom of being a teenager in a rural Australian town.

The same kinds of drawings can be found on the couch in Camera Familiaris (Family Room), along with the trademark symbols of again, bored youth. Part of this section includes a hallway featuring works from the artist’s history, and a common-looking image of Mary and Jesus. The room reeks of the disinfectant Dettol, which the artist says was used in his household not only to clean, but to clear undesirable odours.2Camera Familiaris is also eerie—a cathode ray tube television in the corner, a bike with no wheels (the artist says that this is a nod to feeling like there is nowhere to escape to), a bookshelf with books on astral projection and out-of-body experiences, and a tape featuring much the same content. The most disconcerting thing about the room, though, is the old kerosene fridge common to Australian households in Moore’s youth. You can smell it just by looking at it. It emanates a breathing sound, which the artist says is a memory of being locked in the fridge as a child (he does not remember whether this memory is 100% true). The whole room just feels as though you are trapped in it—from the fridge, to the bike frame, to the yearning to be somewhere else as referenced in the material on astral projection.

Smell is one of the senses that Moore has often worked with. In 2014, the artist created a suite of perfumes that linked with memories of smells that were familiar to his childhood. Made for The Commercial (his representative gallery), the artist worked with a perfumer to produce these seven olfactory works, including the smells of graphite pencils, paper and of Brut aftershave lotion combined with rum.3 The use of more senses than just sight in Moore’s practice allows the artist to express memory more thoroughly and evocatively, but it also deflects the notion that one must experience culture only with the eyes. In Galileo’s formulation of the rational (science) and the emotional (art), he set up a binary in which the emotional and the ‘rational’ were polar opposites. As Robin Dunbar notes in The Trouble With Science, ‘On the one hand, the proponents of science, enthused by its dramatic successes, rushed headlong down the sometimes bewildering maze of corridors opened up by scientific revolution. On the other, the reaction against the hard-edged world of science found expression in yearning for a more emotionally sensitive relationship with nature.’4 Moore, in his rejection of these binaries, allows the emotional and the rational to intersect in a way that both cherishes methodologies toward knowledges that have been less commonly practiced in Australia since colonisation, and admonishes the ways in which contemporary Australian society shuns emotion, and the emotionally vulnerable. In Archie Moore: 1970 – 2018, the artist has both enlivened (Dettol smells) and constrained (in a dark room, you have to depend on senses other than sight) the senses, creating a tension that allows a multitude of readings.

And this is not the first time that Moore has delved into memory within domestic space. In 2010, the artist created a tender work, Dwelling at the now defunct Brisbane artist run initiative, Accidentally Annie Street, an old Queenslander in an inner-city suburb of Brisbane. The exhibition ran through the house, with similar (but not the same) paraphernalia in the living room, but also extending to the bathroom, and the kitchen. Each room featured different props, papers, toys, and Grubannax’s familiar graffiti. Here, the mnemonics felt lived in (the house was in fact lived in), which allowed viewers—mostly those familiar with the artist and friends of the gallery—to feel ‘at home’. In Archie Moore: 1970 – 2018, a connection to the artist’s own memories felt a little more disconnected, less lived-in, but still visceral and less trapped.

Camera Obscura, which was accessed through the middle door, is its own single room, separated from the ‘house’—almost like an outhouse. It uses a camera obscura to project an image of the world outside. That is, the entryway to the gallery. As your eyes adjust to the room, you notice the comings and goings of people outside, but feel as though you are in a broom closet. Here, the artist asks us to question perceptions of reality—how ideas are formed, and how one can relate to something external to oneself. It is theatrical, not in the way that the image is moving, but in the way that you are questioning if something is really happening in the way that it is presented.

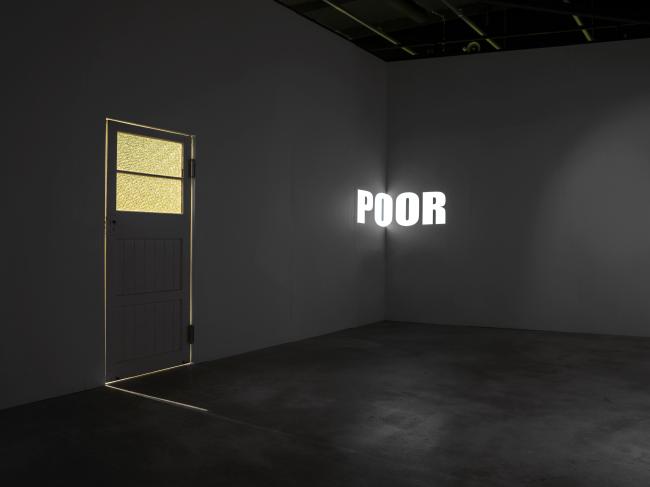

Camera Affecta—a darkened room—is one of the most emotionally affecting rooms in the exhibition—it could be traumatic or peaceful, depending on what state of mind you are in while inside. It is dark, fog fills the room, and the only light you can see comes through a shuttered door. It is as though you can feel life outside and only use your imagination to deduce what that life may consist of. Again, this is a theatrical work—theatre is a good means for embodying emotion. The theatricality of Moore’s work is pared back—not devoid of narrative, but open to interpretation. The overall effect is that the whole of Archie Moore: 1970 – 2018 feels as though it is a set, without actors, where each individual object or sensation brings forth a certain cue in the memory of each person experiencing the show.

In the hallway leading to the gallery entrance, Moore constructed a large family map, which also alludes to memory, imagination, and holes in stories. Starting with Moore at the bottom, it traces up to his parents and their parents and so on. The genealogy, however, is less than exact. Access to family lineages is often difficult due to the processes of colonisation in Australia, and in this map, Moore has even made up names (or named people after famous Australians) to fill the gaps. There are also three great puncture wounds—as though guns have been shot through the map, alluding to schisms in his family’s history; parts that were lost due to colonisation. It is a brutal view, but it also pays homage to his forebears. Here, the artist’s uncertainty with his own memory, and the imagination used to conjure up a perception of himself, are all evident. It is also testament to the living cultures that existed long before 1788 in what we know as Australia.

The use of made-up names in the aforementioned work is also a tactic that the artist employed in his flag works: United Neytions (2017), shown in The National: New Australian Art (2017) in Sydney, and in 14 Nations (2014), shown as part of Courting Blakness: Recalibrating Knowledge in the Sandstone University (2014), at the University of Queensland. The flags are representations of the Indigenous Nations that amateur surveyor R.H. Mathews mapped in 1900. Researching Mathews’s ‘countries’, the artist made flags for each of the nations depicted—they were approximations of what a country could use as symbology—sometimes drawn from local mythologies and symbols, and other times, completely fabricated.

Returning to language, Camera Verbum is one room which features two projections facing into corners, like shunned school kids. On one side, words that Moore heard inside his childhood home are flashed up, and on the other side, words that he heard outside. These words and phrases switch between positive and negative, constructive or downright racist on both walls—‘Wild Black’, ‘Handsome Young Man’, ‘Listless’, ‘Fuck Me Rome’, ‘Wouldn’t Work In An Iron Lung’, ‘Dumb’, ‘Lazy’, ‘Abo’, ‘What Colour is Archie?’. In the corners, set into the walls, were a pair of knitted booties, a clay pipe, and a cockroach, all symbols associated not only with family and home—in Queensland at least—but also symbols of colonisation.

Archie Moore: 1970 – 2018 is a triumph in that its use of imagination allows us all to think through our interactions with the world around us, and question the ways that we interact with other people in it. It is confined to one gallery, but the worlds inside are so vast, you could live a lifetime in them. Archie has.

Archie Moore: 1970—2018, Griffith University Art Museum, 2018. Installation view, gallery reception. Photograph Carl Warner. Courtesy the artist and The Commercial, Sydney.

Camera Aviae, 2018. Archie Moore: 1970—2018, Griffith University Art Museum, 2018. Installation views. Photograph Carl Warner. Courtesy the artist and The Commercial, Sydney.

Camera Verbum; 2018. Archie Moore: 1970—2018, Griffith University Art Museum, 2018. Installation details. Photograph Carl Warner. Courtesy the artist and The Commercial, Sydney.

Camera Schola, 2018. Archie Moore: 1970—2018, Griffith University Art Museum, 2018. Installation views. Photograph Carl Warner. Courtesy the artist and The Commercial, Sydney.

1. A. Goddard, ‘Archie Moore: Memory Descriptions’ in Archie Moore: 1970—2018, Griffith University Art Museum, Brisbane, 2018, p.11.

2. Author’s conversation with the artist, March 2018.

3. B. Dean, ‘Archie Moore – Les Eaux d’Amoore’, exhibition essay, The Commercial, Sydney, 2014.

4. R.I.M. Dunbar, The Trouble with Science, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass.,1995, p.i.